This story, which happened forty years ago next month, tells how a tiny upstart record label, a couple of white poker-playing pill-popping hipsters and a black vocalist steeped in the traditions of the Baptist church created a masterpiece: The Dark End of the Street.

It is set in Memphis, where that kind of thing used to happen regularly.

Quinton Claunch, founder of Goldwax, the aforementioned tiny label, had been something of a fixture on the Memphis music scene since 1952. Sam Phillips had hired him and Bill Cantrell as session musicians and talent scouts for his then fledgling Sun label. Guitarist Claunch and fiddle player Cantrell had been in the hillbilly band the Blue Seal Pals together in the Forties. At Sun they played on and co-wrote tracks for Carl Perkins, The Miller Sisters and Charlie Feathers.

“I got to love R&B because Sam would follow a country session with an R&B session and it was impossible not to hear it.” Claunch recalled in Barney Hoskyns' book Say it One Time for the Broken Hearted.

In 1956, together with sometime rockabilly singer Ray Harris and record shop owner Joe Cuoghi, Cantrell and Claunch founded Hi Records. Destined to become another of Memphis’ legendary labels, Hi’s first release was the Claunch/Cantrell composition Tootsie performed by Carl McVoy, a piano playing cousin of Jerry Lee Lewis. Although this initial release was a small success Hi only really limped along until 1959 when the label finally enjoyed its first big hit: Smokie- Part 2 an instrumental by the Bill Black Combo. Black had quit his job as slap bass player for Elvis Presley the year before and was a long time friend of Ray Harris. After the success of Smokie-Part 2 Harris assumed more and more of the production duties at Hi, much to Claunch’s chagrin who quit the label and sold his share in it to Carl McVoy in 1960.

Claunch founded Goldwax with $600 from Rudolph ‘Doc’ Russell, a Memphis pharmacist in 1964. The labels first release, Darlin’ by the Lyrics, was recorded at the FAME studios in Muscle Shoals and, despite being Claunch’s first real attempt at R&B, was a large enough hit to attract the attention of London Records:

“So one day I get a call from a guy at London Records about distributing the record, and then he came into town and picked up the master. It took them about two or three weeks to get it all processed and to put it out, and by that time the record was dead, and we were back in debt. I always thought Joe Cuoghi killed it, though I couldn’t ever prove anything, but Hi was distributed by London, of course, and it just made sense.” remembered Claunch (from Sweet Soul Music by Peter Guralnick)

However Claunch’s luck picked up one night when medical technologist and aspiring music impressario Roosevelt Jamison showed up on his doorstep:

"I heard a knock on my door about midnight," recalls Claunch. "So I got up,went to the door and there stood O. V. Wright, James Carr and Roosevelt Jamison."They told me (Stax head) Jim Stewart had sent them by and they'd like for me to listen to a tape. We sat down in the middle of the living room floor and the voices just knocked me out. I asked them what they had in mind and they said, `Man, we want to cut a record.' "(from James Carr’s obituary in The Commercial Appeal by Bill Ellis)

And that’s exactly what they did.

O.V. Wright recorded Jamison’s composition That’s How Strong My Love Is for Goldwax sixth release in 1964. Jamison had taken the song to Stax but had believed them uninterested when O.V. Wright cut the track. Claunch could be forgiven cursing his luck when Otis Redding released his version shortly after the Goldwax release.

Worse than that, Peacock Records owner Don Robey had the Sunset Travellers, a gospel group that Wright sang with, under contract and he put out an injunction to prevent the solo release. Claunch and Russell came to an agreement with Robey whereby they gave up their claim to the artist but maintained the rights to the single. Wright never recorded for Goldwax again.

Speaking to Tim Perlich for Soul Survivor magazine in 1988 Roosevelt Jamison said:

“Y'know, personally, I doubt that any such contract between O.V. and Don Robey ever existed. If there was, I never saw it. That was only part of the reason why O.V. left Goldwax though. O.V. had an engagement to do a show in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, for some local D.J. named Dickie Doo, but Quinton Claunch refused to give us the money for gas to get there. Ricky Sanders, Earl Forrest and I went with O.V. and did the show anyway, but after that incident O.V. went straight to Texas.”

With Wright’s depature the label concentrated their efforts on the other singer that had arrived that night: James Carr.

Carr’s father was a Baptist preacher and Carr had been singing in church since he was six years old. At nine he had joined the gospel quartet the Harmony Echoes.

Carr remembered: “Me and Roosevelt were involved with two gospel groups, the Harmony Echoes and the Sunset Travellers. When my mother and father died, I stopped singing gospel.” (from Tim Perlich’s interview in Soul Survivor Number 9, Summer 1988)

Carr’s first Goldwax release also came in 1964 and was another Jamison composition, You Don't Want Me; it was largely overlooked on release. It wasn’t until 1966 that Carr hit with the O.B. McClinton composition You’ve Got My Mind Messed Up which reached number seven in the Billboard R&B charts and stayed there for two months.

Many of Goldwax sides where cut at Muscle Shoals FAME studio under Rick Hall’s guidance. The Dark End of the Street’s co-writer Dan Penn was something of a fixture at Hall’s studio and recalled meeting Claunch and his partner Russell there:

“They brought Spencer Wiggins, The Ovations, James Carr, maybe O.V. Wright - seems like O.V. cut most of his stuff in Memphis. We were familiar with Doc and Quinton because they came to FAME (Rick Hall’s studio). I remember taking Doc Russell's '64 Caddy out to get hamburgers. Yeah, I remember the night when I drove that big Caddy.” (from Joss Hutton interview for Perfect Sound Forever)

It was ‘Doc’ Rusell who first mentioned The Dark End of the Street's other writer, Chips Moman, to Penn:

“Doc Russell says to me ‘Man there’s guy in Memphis that’s just like you. Looks like you, acts like you, plays like you’ I said ‘Aw, shit, well I’ll just have to meet that dude.’…When we met, we just went ‘Pssht!,’ just like that, cause, see, he had heard the same thing about me.” (from Sweet Soul Music by Peter Guralnick)

Moman and Penn met in spring 1966 and hit it off right away. Moman and Penn shuttled between each other respective home bases: Muscle Shoals for Penn, Memphis for Moman. As Moman said “Dan’s one of the reasons I went to Muscle Shoals to start with. I wanted him so bad to write and produce and work up in my studio in Memphis that I would play down there on sessions” (from Sweet Soul Music by Peter Guralnick)

Georgia native Lincoln Wayne ‘Chips’ Moman had arrived in Memphis in 1960 after working as a session musician in California with, amongst others, Gene Vincent and the Burnette Brothers. He had fallen in with Jim Stewart and Esttelle Axton who at that time ran the struggling Satellite label out of a garage. Moman it was who located the old movie theatre on East McLemore and helped convert it into the recording studio where so many classics were recorded for Stewart and Axton’s renamed Stax label. By ’66 however Chips had left Stax behind and was working his own studio: American Recordings.

Penn recalls: “Chips had a radio board back then and a 350 Ampex, actually he had two Ampex mixers, he didn’t hardly qualify as a studio” ( Sweet Soul Music Peter Guralnick)

Still, what Chips did have was a first rate studio band made up of guitarist Reggie Young, who as part of Bill Blacks Combo had played on Smokie - Part 2, Bobby Wood on piano, Gene Chrisham on drums, Bobby Emmons on organ and Mike Leech on bass. American Recordings had their first hit in 1965 when The Gentrys Keep on Dancing reached number four on the pop charts. Moman never liked the song and told Memphis based writer Jim Dickerson that “he hated the song so much he mixed it with the sound turned off, setting the mix by the meter alone.”(Goin’ Back to Memphis James Dickerson).

The same year as The Gentrys hit Penn finally scored a hit record with I’m Your Puppet for James and Bobby Purify:

“During the four years with Rick I realized the facts - the facts were that all these songs I'd written I thought were great weren't worth a damn and I had to make adjustments if I wanted to make a songwriting career. I had to adjust my thinking. Me and Rick would always take reels of tapes to Nashville - to Chet Atkins and Mr Owen Bradley - and we take 'em in and they had us run the tape for 'em. [Dan imitates the sounds of an old tape machine being forwarded and played numerous times] Well, I'm getting highly pissed after ten songs of that and on the way back home I'm saying to Rick "Why didn't they listen to the whole damn songs?" and he said "I don't know!”He didn't have a clue! But I finally figured it out and one day changed direction and thought "I'm gonna start putting the title right up front!" So during that era the title - Dark End of the Street it starts immediately, I'm Your Puppet is right in there - they just get 'em. Five, ten bars, that was my whole deal, the very beginning.”( from Joss Hutton interview for Perfect Sound Forever)

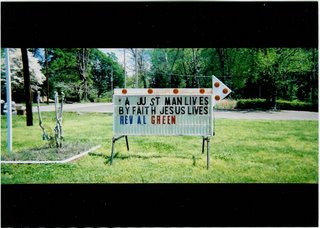

Penn moved to Memphis in the summer of ‘66. It was during a DJ convention that summer that The Dark End of the Street was written: “Chips and Dan Penn had come to my room,” recalled Claunch, “poppin’ pills and playin’ poker- and they sat down and started to write a song. So I said ‘boys, you can use my room on one condition, which is that you give me that song for James Carr. They said I had a deal, and they kept there word.” (Say it One Time for the Broken Hearted Barney Hoskyns)

Penn says: “We was playing poker with (Florida DJ and producer of the Purify Brothers) Don Schroeder, and me and Chips was cheating him. Anyways we took a break, wrote the song, and I told Chips, ‘Let him get his fucking money back or I’m spilling the beans’. Now Moman’s a great poker player, got real fast hands and we let him win his money back” (Sweet Soul Music Peter Guralnick)

Written in about thirty minutesThe Dark End of the Street is a tale of adultery told from the adulterer's point of view. It is an inherently dramatic song. The adulterer knows that what they are doing is wrong but (and this is the crunch) is in the grip of a passion so much greater than "ordinary" moral concerns that they are helpless in the face of it, even if the affair is not making them happy.

“We were always wanting to to come up with the best cheatin’ song. Ever.” Penn told Robert Gordon for his book It Came from Memphis.

The Dark End of the Street was tracked at Hi studios initially and then James Carr was brought to American to do vocal overdubs. Moman, who engineered the session, said of Carr: “I could have sat and listened to him all day” (Say it One Time for the Broken Hearted Barney Hoskyns) and Penn agreed “We thought James was fantastic; he had made some good records before, and we knew we had made a good record.” (from the Proper Records website)

"It's really a simple song. Just sing it the way you talk. It's just easy, and I arranged it by the way I read it, the way I read the words. Didn't really have the music to it then, I arranged it by the way the words were." Carr told Robert Gordon when he interviewed him in the early nineties for Q magazine.

Released in 1967 The Dark End of the Street failed to chart as highly as You’ve Got My Mind Messed Up stalling at number ten on the Billboard R&B charts.

It has been been covered many times since there were at least three other versions in 1967 alone including one by Oscar Toney Jr that Moman himself engineered.

Artists as diverse as Aretha Franklin, The Flying Burritto Brothers and more recently Frank Black have covered it. Speaking of the version he did for his Dan Penn produced album Honeycomb, Black remembered “"(Dan Penn) went in and sang it and it was like smokin' and then he says ' Let's stop fucking around, let’s play a real version!' And then he sang the most haunting version of it! How can I follow that?" (Mojo 141 August 2005)

Although trailing James Carr's by several country miles I have a soft spot for Porter Wagoner and Dolly Parton’s 1968 version, produced by Bob Ferguson, for their Just the Two of Us album, the song works well as a male/female duet with both parties equally culpable and damned.

“I’m a James Carr fan myself”, Dan Penn told Barney Hoskyns for The Independent on Sunday's Lives Of The Great Songs series “The other versions, I’m glad they cut ‘em and God bless ‘em for it but compared to James Carr’s there are no other versions.”

When I listen to Carr’s version, especially the haunted, hunted way he howls “They’re gonna find us…”, I am reminded of the fact the men behind this song lived with the evil of segregation and that these men, these free spirits, in all of Memphis’ little recording studios, all of which are somehow implicated in the creation of this masterpiece, rejected that evil and showed, in the creation of their art, that there was another, better way.